Insisting on the Rights of Everyone Everywhere

By Howard Zinn, excerpted from The Zinn Reader

By Howard Zinn, excerpted from The Zinn Reader

I was one of the speakers at historic Faneuil Hall in Boston (though named after an early slave trader, it was the scene of many meetings of anti-slavery groups before the Civil War) in 1991, when the Civil Liberties Union of Massachusetts organized a celebration of the Bicentennial of the Bill of Rights. I wanted to use the opportunity to make clear that whatever freedoms we have in the United States—of speech, of the press, of assembly, and more—do not come simply from the existence on paper of the first Ten Amendments to the Constitution, but from the struggles of citizens to bring those Amendments alive in reality.

________________________________________

A few years back, a man high up in the CIA named Ray Cline was asked if the CIA, by its surveillance of protest organizations in the United States, was violating the free speech provision of the First Amendment. He smiled and said: “It’s only an Amendment.”

And when it was disclosed that the FBI was violating citizens’ rights repeatedly, a high official of the FBI was asked if anybody in the FBI questioned the legality of what they were doing. He replied: “No, we never gave it a thought.”

We clearly cannot expect the Bill of Rights to be defended by government officials. So it will have to be defended by the people.

…

If it were left to the institutions of government, the Bill of Rights would be left for dead. But someone breathed life into the Bill of Rights. Ordinary people did it, by doing extraordinary things. The editors and speakers who, in spite of the Sedition Act of 1798, continued to criticize the government. The Black and white abolitionists who defied the Fugitive Slave Law, defied the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, who insisted that Black people were human beings, not property, and who broke into courtrooms and police stations to rescue them, to prevent their return to slavery.

L-R: Black abolitionists played crucial roles in assisting people escaping and to abolish slavery; the Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers stopped Kentucky “slave-catchers” from kidnapping John Price; and Christmas fairs raised money for anti-slavery activities.

Women, who were arrested again and again as they spoke out for their right to control their own bodies, or the right to vote. Members of the Industrial Workers of the World, anarchists, radicals, who filled the jails in California and Idaho and Montana until they were finally allowed to speak to working people. Socialists and pacifists and anarchists like Helen Keller and Rose Pastor Stokes, and Kate O’Hare and Emma Goldman, who defied the government and denounced war in 1917 and 1918. The artists and writers and labor organizers and Communists—Dalton Trumbo and Pete Seeger, and W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, who challenged the congressional committees of the 1950s, challenged the FBI, at the risk of their freedom and their careers.

L-R: The Silent Sentinels demonstrating for the right to vote; Hattie Canty, labor organizer; Asian immigrants demanding better work conditions; and marchers at the Moral Monday March & Interfaith Social Justice Rally.

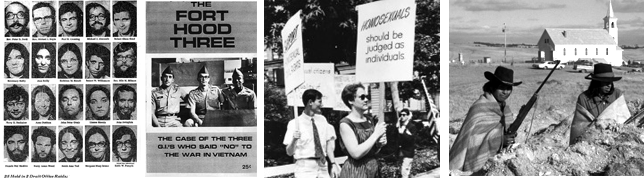

In the 1960s, the students of Kent State and Jackson State and hundreds of other campuses, the draft resisters and deserters, the priests and nuns and lay people, all the marchers and demonstrators and trespassers who demanded that the killing in Vietnam stop, the GIs in the Mekong Delta who refused to go out on patrol, the B-52 pilots who refused to fly in the Christmas bombing of 1972, the Vietnam veterans who gathered in Washington and threw their Purple Hearts and other medals over a fence in protest against the war.

And after the war, in the ’70s and ’80s, those courageous few who carried on, the Berrigans and all like them who continued to demonstrate against the war machine, the Seabrook fence climbers, the signers of the Pledge of Resistance against U.S. military action in Central America, the gays and lesbians who marched in the streets for the first time, challenging the country to recognize their humanity, the disabled people who spoke up, after a long silence, demanding their rights. The Indians, supposed to be annihilated and gone from the scene, emerging ghostlike, to occupy a tiny portion of the land that was taken from them, Wounded Knee, South Dakota. Saying: we’re not gone, we’re here, and we want you to listen to us.

L-R: Mugshots of the Camden 28, religious protesters who destroyed draft records; Fort Hood Three, soldiers who protested Vietnam; first Annual Reminder march for gay and lesbian rights in 1965; and defenders at Wounded Knee.

These are the people, men, women, children, of all colors and national origins, who gave life to the Bill of Rights.

…

In the real world, the fate of human beings is decided every day not by the courts, but out of court, in the streets, in the workplace, by whoever has the wealth and power. The redistribution of that wealth and power is necessary if the Bill of Rights, if any rights, are to have meaning.

The novelist Aldous Huxley once said: “Liberties are not given; they are taken.” We are not given our liberties by the Bill of Rights, certainly not by the government which either violates or ignores those rights. We take our rights, as thinking, acting citizens.

And so we should celebrate today, not the words of the Bill of Rights, certainly not the political leaders who utter those words and violate them every day. We should celebrate, honor, all those people who risked their jobs, their freedom, sometimes their lives, to affirm the rights we all have, rights not limited to some document, but rights our common sense tells us we should all have as human beings. Who should, for example, we celebrate?

I think of Lillian Gobitis, from Lynn, Massachusetts, a 7th grade student who, back in 1935, because of her religious convictions, refused to salute the American flag even when she was suspended from school.

And Mary Beth Tinker, a 13-year-old girl in Des Moines, Iowa, who in 1965 went to school wearing a black armband in protest against the killing of people in Vietnam, and defied the school authorities even when they suspended her.

An unnamed Black boy, nine-years-old, arrested in Albany, Georgia, in 1961 for marching in a parade against racial segregation after the police said this was unlawful. He stood in line to be booked by the police chief, who was startled to see this little boy and asked him: “What’s your name?” And he replied: “Freedom, freedom.”

I think of Gordon Hirabayashi, born in Seattle of Japanese parents, who, at the start of the war between Japan and the United States, refused to obey the curfew directed against all of Japanese ancestry, and refused to be evacuated to a detention camp, and insisted on his freedom, despite an executive order by the president and a decision of the Supreme Court.

Patty and Alex Rodriguez hold a framed photo of their father, Demetrio Rodriguez. Image: Mark Sobhani/Houston Public Radio.

Demetrio Rodriguez of San Antonio, who in 1968 spoke up and said his child, living in a poor county, had a right to a good education equal to that of a child living in a rich county.

All those alternative newspapers and alternative radio stations and struggling organizations that have tried to give meaning to free speech by giving information that the mass media will not give, revealing information that the government wants kept secret.

Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner, refused to pay federal taxes as a protest against war and military spending.

All those whistleblowers, who risked their jobs, risked prison, defying their employers, whether the government or corporations, to tell the truth about nuclear weapons, or chemical poisoning. Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner, who have refused to pay taxes to support the war machine, and all their neighbors who, when the government decided to seize and auction their house, refused to bid, and so they are still defending their right.

The 550 people who occupied the JFK Federal Building in Boston in protest when President Reagan declared a blockade of Nicaragua. I was in that group—I don’t mind getting arrested when I have company—and the official charge against us used the language of the old trespass law: “failure to quit the premises.” On the letter I got dropping the case (because there were too many of us to deal with), they shortened that charge to “failure to quit.”

I think that sums up what it is that has kept the Bill of Rights alive. Not the president or Congress, or the Supreme Court, or the wealthy media. But all those people who have refused to quit, who have insisted on their rights and the rights of others, the rights of all human beings everywhere, whether Americans or Haitians or Chinese or Russians or Iraqis or Israelis or Palestinians, to equality, to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. That is the spirit of the Bill of Rights, and beyond that, the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, yes, the spirit of ’76: refusal to quit.

No comments:

Post a Comment